Israelis show us: torture simultaneously conditions both prisoner and guard

Through sadism, the IDF transmogrifies into one beating blob of inhumanity

It’s been said that a novice may look at someone in front of them and be unaware of what they are seeing, but put an experienced practitioner in front and they will notice right away that the subject has a condition, whether or not the subject knows it him- or herself. Perhaps it’s a limp, or a slight sag in the cheek. The untrained eye will glide right past these features, but a doctor, especially a clinician who sees thousands of patients over the span of his or her practice, realizes with just a glance.

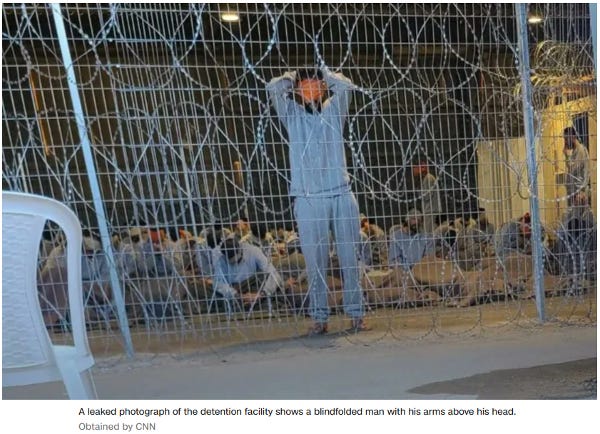

As I watched a clip reviewing a CNN investigative report, released just last week, that detailed conditions at what some are calling a concentration camp (some might say “black site” or undisclosed detention), I had that moment myself, where I recognized something that the ordinary viewer or reader may never have been able to place.1

What’s described in the CNN report actually lies at the nexus of three different strands of extremism: thought reform, cult formation, and torture techniques.

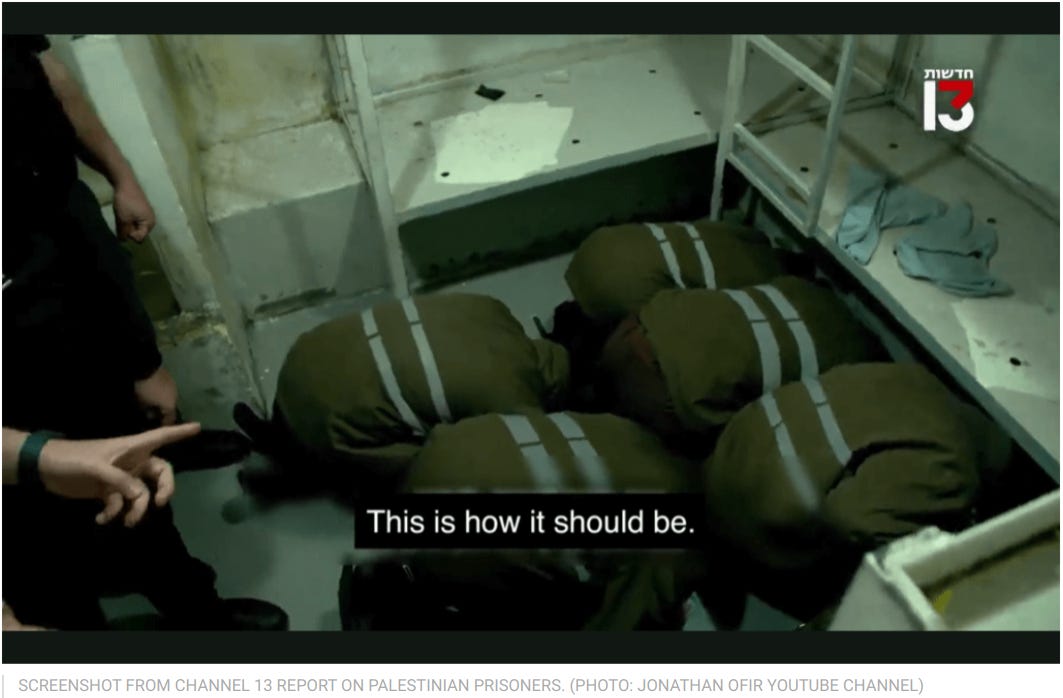

CNN noted that Palestinian men, en route to Sde Teiman, Israel, were stripped nearly naked and crammed into the back of a truck as they were being transported to this black site in the middle of the desert. The person interviewed said that the near-naked men were piled just about on top of each other.

This matches reporting we had heard months ago, including one tale told from the perspective of a lone female, who had been subjected to similar conditions with men. These conditions are highly humiliating for all involved.

Clearly, this recalls the sadism displayed by Americans at Abu Ghraib. But it also recalls episodes of extreme hazing that occurs in hierarchical private societies such as fraternities and other secretive groups. Of course, the prisoners here were not attempting to gain access to exclusive clubs, but those imparting the torture may gain a benefit — esteem among the other torturers.

The CNN report focused on one prisoner, Mohammed Al-Ran, a doctor, who was kept for weeks in unconscionable conditions.

Once the Israelis cleared him of suspicion, finding that he had no ties to Hamas or other militant groups, they did not release him, however. They kept him on, according to CNN, as “an intermediary between the guards and the prisoners, a role known as Shawish, ‘supervisor,’ in vernacular Arabic.”

This may bring to mind for some the position of kapo in Nazi concentration camps, those Jewish prisoners who had been selected to stand guard over the others. Kapos served as middlemen and received minor rewards for their service. Generally, kapos were despised by the other prisoners — this was almost a universal view among the prison population.

One might also think of the field hands in slavery who worked directly below the overseer, the enslaved folks who made sure that everyone else kept pace. They, too, earn the ire of many of their charges, not only because of the benefits that the middlemen received but because, oftentimes, those men handed out the harshest reprisals to those who lagged behind and disrupted the work rhythm.

However, I saw that detail and gasped, knowing where I had seen something similar.

It immediately brought to mind a passage from Robert Jay Lifton’s Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism. Lifton’s work shone a spotlight on certain techniques employed by China in the 1950s meant to coerce more or less permanent attitude changes on political prisoners, techniques we today would colloquially call brainwashing. (This phenomenon was hot news back in that era, due to the condition of POWs returning home from Korea.) In terms of what China was doing at that time with its Western prisoners, Lifton revealed:

The Europeans were brought into the cell one by one, for the apparent purpose of “helping” each other with their confessions and reform. The early pattern was essentially as follows. One European who had achieved some degree of adaptation to his environment by making a satisfactory confession and taking part in the criticism of others would be joined by a second Westerner who was still in acute conflict over how much to submit. . . . Always present, in combinations only partially understood by himself, were a genuine desire to help a fellow Westerner to accept the inevitable; an attempt to demonstrate his own “progressiveness” to the authorities in order to gain “merits” toward release; and the need to justify his own self-surrender through bringing a person similar to himself into the sphere of those who have already surrendered — a way to share guilt, shame, and weakness.2

The experienced prisoners were shepherding the rookies, appearing as a form of stability, as bedrock, all the while easing the newcomers into the very system that would undermine their hold on reality.

Dr. Al-Ran also told of being permitted a special privilege: that of removing his blindfold. Most other detainees were blindfolded their entire time in the camp.

(While Dr. Al-Ran had misgivings about the ability to witness such terrible acts being committed against other detainees, the removal of the blindfold would have also been accompanied by a sense of relief at being able to accurately sense one’s environment. That’s a natural reaction.)

This detail brought to mind descriptions by psychologists of the 1950s who warned of the moral injury inflicted upon American POWs in Korea:

Besides the schoolroom approach of repetition of information by the same instructor, round-table seminars in the evening, and the offering of only [narrow, ideological] literature to read, the captors also offered minor favors of more tobacco or more sugar to those who showed a greater tendency to cooperate. […]

On Thanksgiving of 1951, the POW's were asked to write a note of appreciation about the chicken and bread dinner they had received. Those who wrote good reports were rewarded by having them pasted with a red star and placed on a bulletin board.3

One prisoner was forced to sing party-line songs and write ideological statements in favor of his captors:

Although at first he probably did not accept these, he was rewarded for these activities, and consequently the behavior must be considered as having been reinforced. The role of a high-drive state as a result of hunger and the assuagement of the hunger as a reward must be taken into account. Further, he was given tasks to accomplish by his captors and received various types of gratification for these activities.4

According to the authors, these favors, interspersed with harsh treatment, resulted in “rather intensive brainwashing.”5

The interweaving of punishment and reward is essential for creating a state of disorientation. Joost Meerloo, a psychologist from midcentury, described this process, something he called menticide:

The system starts with verbal conditioning and training by combining the required stereotypes with negative or positive stimuli: pain, hunger, or a reward. Often a threat of death is used. . . Hunger and food were mostly the negative and positive stimuli. For resisters, other forms of torture are used. The gamut of negative stimuli consists of physical pressure, moral pressure, fatigue, hunger, chemical pressure (narcotics), boring repetition, confusion created by seemingly logical syllogisms. And when the victim asks for logical sense or personal understanding and reacts with intelligent protest he has to be broken down systematically.

He is told that he is betrayed by his mander, that nobody is there any more to help him. He can starve and die without anybody knowing about him and his heroism. He is alone and helpless. Guilt and fear are provoked alternately, and he receives rewards when he speaks and acts the right way. Many of the victims were first brought to a state of mental disintegration and confused depersonalization in order to distort their sense of values, then nearly brought to the point of suicide or even to suicide itself.

This kind of Pavlovian strategy arouses in everybody a “confusion neurosis” — a general feeling of irreality. It leads gradually to complete mental submission and willingness to play any role.6

This was confirmed by William Sargant, a physician, also writing during this time of heightened concern about the integrity of an individual’s personality and the threat that thought reform posed to that sanctity. Speaking of interrogation methods employed by the Soviet Union under Stalin, Sargant said, “[E]very effort was made to stir up anxiety, to implant guilt, to confuse the victim, to create a state in which he does not know what is going to happen to him from one minute to the next.”7 It is well-known that sensory deprivation, such as the placement of blindfolds, contributes to this sense of disorientation and confusion.8

This process is valuable both when breaking down detainees as well as reshaping attitudes in high-intensity groups. When both the breaking down of one group and the reconstruction of another are in evidence simultaneously, we can speak of a system of dual conversion.

(Some readers may have skepticism with regards to the process just described, but it is one that is recognized by specialists in the social sciences. Also, it shares many features with an adjunct yet very similar process involved in the fashioning of recruits in high-intensity groups, something I address below.)

Another section of the CNN report spoke of the extreme stress positions these men suffered:

Recalling a tradition with roots extending back to at least the Inquisition, this type of maltreatment illustrates the undermining of a person’s psychological foundations and the symptoms that surface as a result. William Gorman, in a joint presentation called “Torture, Law, and War: Psychology and Torture,” detailed what torture imparts:

disruptions of memory, disruptions of concentration, falling prey to rumination, obsessing over the incident in question;

depression, anxiety, anger, confusion;

learned helplessness;

loss of trust, loss of sense of identity, loss of community, marginalization;

post-traumatic stress disorder (tendency to avoid any situations that are reminders, social withdrawal, hyperarousal, hypersensitivity; nightmares, intrusive memories, flashbacks; emotional numbing);

And humiliation — it comes from having extreme and arbitrary stress imposed without the ability either to fight it or to flee from it. You’re trapped in it. This is what can induce an animal’s extreme anxiety conditions. It’s the same thing with human beings. It’s one of the psychological effects of torture in the immediate sense.

The isolation and denial is huge: trying to avoid thinking about it, trying to avoid acknowledging that it happened, trying to get on because you can’t face it, that we often find survivor guilt. You can, perhaps, appreciate the significance of it. The sense of shame often happens, even though the person who was victimized should have no reason for shame. They often carry that as well. And, even worse, a self-blame. They feel somehow, “It was my fault that this was done to me.” They blame themselves. They can work their way through that, but the blame is an important effect of this experience.9

Gorman highlighted a more invidious form:

I think the psychological torture is the preferred way to torture people rather than the physical. The physical is more brutal, but it’s also more seen. And it also, they find, that it’s not even very effective at getting information, that under the physical torture people will say anything to stop it. They try to use the psychological torture to break their will, break their will to resist. One book on it calls it the breaking of the mind and the body: to shatter the person, so that their own sense of efficacy is no longer in play.

The psychological means are used more often: that is, sensory deprivation, humiliation, the shaming, the guilt, the violation of one’s own values — the use of the Quran, for example, or smearing of faces with menstral blood. These don’t leave bruises on the body, but they can certainly leave bruises on the psyche, if you will.

So the psychological are considered the soft, the lighter, torture, but in some ways they’re the more powerful and the more profound, and they have more lasting effects[.]10

Yet what occurred at Sde Teiman far exceeds even these outliers of extremity mentioned by Gorman, because CNN reports that the Israelis didn’t exact these methods to extract information — they did it purely as payback. It was revenge and retaliation, a remnant of rage:

That’s a different class of torture. That’s almost pure sadism.

Hannah Arendt noted that some Nazi soldiers ended up with nearly a split or double personality, where on the one hand they would deliver the most inhumane treatment to their prisoners but on the other go home and be the model spouse and parent once off-duty.11

Christopher Browning, author of Ordinary Men, said that the German regime screened out sadistic and unbalanced folks, but about a third of the soldiers that entered the SS discovered that trait within themselves as time went on. (Other authors have corroborated this fact.)

Philip Zimbardo, the sociologist who served as the warden of the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, found the same trend in his college-aged “prison guards,” who had been carefully screened so as to be well-balanced, regular guys without any traits that might lend themselves to furthering abuse.12 About one-third of the guards turned vindictive and sadistic, with a few taking it upon themselves to devise new ways of punishing the prisoners; one-third kept mum and followed the lead of these sadists; and another third gave clandestine help to prisoners when they thought no one else was looking.

What these guards were arranging, whether they knew this or not, was a system of ultra-bonding among the abusers. This has been documented in torture camp systems in other places, where new recruits are gradually broken into being an interrogator, first by something relatively innocuous, such as guarding outside of a cell while a prisoner is worked over; then perhaps getting closer to the action, inside the cell, watching more experienced practitioners and observing the techniques; then ultimately taking over more and more of the physical aspects of interrogation, until they become seasoned and hardened to the practice.

All the while, the recruit is bonding with the veterans. He becomes sealed in the system. As he joins in on acts of power and domination, he becomes subsumed into the group, the greater whole.

As was said before, “Although at first he probably did not accept these, he was rewarded for these activities, and consequently the behavior must be considered as having been reinforced.”

And it’s this aspect that is eerily similar to bonding rituals in high-intensity groups — cults. Leaders of such groups will subject recruits and more experienced members (paired together in the “buddy system”) to extreme situations where they all must participate. Through the ordeal, the recruits and established members grow closer as a result of overcoming whatever obstacle they had to defeat or experience they had to endure. This binds the recruit more tightly to the group as a whole, which in turn increases the likelihood a “double personality” or parasitic double may emerge; and it’s this personality that becomes part of the group structure. This is why cults are like that.

Psychologist Boris Sidis, in Studies in Psychopathology, gave an account:

During the [psychological] attack the patient may preserve his personal consciousness fully or but partially. In such a case it appears as if two centers of consciousness are at work, one beside the other and one independent of the other. The patient may be aware of the new independent forces which are foreign to him, but which have apparently taken possession of him in spite of himself. The self seems to be torn in two, and consciousness is doubled. A new incipient parasitic personality is being formed in the recesses of the subconscious, a parasitic personality having a will of its own and no longer subject to the patient’s personal control.13

In high-intensity groups, the experience is not usually felt as an attack, as the recruit has placed him- or herself in that position voluntarily. This very much parallels an IDF soldier fresh in the field. Indeed, the new Israeli soldier has been preparing for the role since childhood — the identity has already been laid down and prepared.

It strikes me as extraordinarily significant that these Israeli troops are undergoing such psychological processes. While the Palestinian prisoners are being atomized — driven to isolation and despair — the Israelis are tightening the ties that bind. Whether or not the soldiers develop a second layer of personality to shield them from their acts of depravity, they nonetheless are becoming brothers through brutalizing those in their custody.

In a different sense, this is reminiscent of passages by Hikmet Karčić, who tells of serial rapes of Bosnian women held in captivity.14 This, in turn, recalls some accounts of rape during the Rwandan genocide. While these particular Palestinian detainees featured by CNN do not report being sexually violated, what I refer to is that deep sense of gaining shared sadistic pleasure among a gang of peers — people who have rank, people from whom one wants to garner respect — at the expense of persons who have lost the ability to respond or resist. It’s a particularly regressive way to discover a sense of superiority.15 But this type of power corrodes a person from within.

As for the Palestinians, they are enduring something I cannot fathom. The sheer scale of atrocity that these people are bearing is almost impossible to contemplate. There is some indication that some may find strength in resilience, once their ordeals are over; but that peace won’t even have the chance to descend upon them until the hostilities are bridled and the weapons silenced.

Importantly, I want to stress that what seems to be a driving goal here of the Israelis is to inflict as much humiliation and anguish among those in captivity as well as the civilian population more broadly. The removal of dignity is the premier end goal. To that end, all of these war crimes are the intended actions of those in command, all the way down the hierarchy. This infliction is what they mean to deliver. Israel’s offensive could not exist were it not for the commission of war crimes. They’re the point.

Now, I don’t claim to be an expert in these things — my degree is not in this particular subject. But I have devoted a lot of the last five years of my life comprehending these phenomena, because I’ve been trying to understand MAGA (and its concentrated extreme, QAnon) as a high-intensity group. So, though I am but a journeyman in this subject matter, I have some familiarity.

Robert Jay Lifton, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China (1961 / 2014), p. 153 (emphases added). Martino Publishing. Originally published by W. W. Norton & Company: New York.

Peter Santucci, M.D., and George Winokur, M.D., “Brainwashing as a Factor in Psychiatric Illness: A Heuristic Approach,” Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry (1955), Vol. 74, No. 1, p. 12.

Ibid., p. 15.

Ibid., p. 16.

Joost Meerloo, “Pavlovian Strategy as a Weapon of Menticide,” American Journal of Psychiatry (1954), Vol. 110, No. 11, p. 810. Paragraph breaks and emphasis added.

William Sargant, Battle for the Mind (1957 / 2011), p. 207. Malor Books. Originally published by Doubleday: New York.

See remarks by Alfred McCoy in his presentation “A Short History of Psychological Terror” (University of California Television, YouTube, February 8, 2008), ~ 16:18.

University of Chicago Law School, “Torture, Law, and War: Psychology and Torture,” YouTube, June 21, 2013, ~ 15:50.

“[P]erversion was artificially produced in otherwise normal men. Rousset reports the following from an SS guard: ‘Usually I keep on hitting until I ejaculate. I have a wife and three children in Breslau. I used to be perfectly normal. That’s what they’ve made of me.’” Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), p. 454, footnote 159. Harcourt, Inc.: New York.

Not only were the students screened for psychological proclivities but each was assigned as a guard or prisoner random allotment. See Haney, Banks & Zimbardo, “Interpersonal Dynamics in a Simulated Prison,” International Journal of Criminology and Penology (1973), Vol. 1.

Boris Sidis, Studies in Psychopathology (1907). D. C. Heath and Company: Boston, MA.

Hikmet Karčić, Torture, Humiliate, Kill: Inside the Bosnian Serb Camp System (2022), p. 202. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

I have noticed remarkable faith in Allah and resilience in the Palestinians. They have dealt with what you describe for 75 years as a culture, but remain unbroken to a surprising degree. I truly admire their strength and am equally horrified by the Israelis' inhumanity.