Racism and sexism figured in Harris's defeat, but not in the way most people think

Through the evocation of bigotry, Trump rang a bell, in more ways than one

A lot of ink has been spilled on speculations as to how it is that Kamala Harris lost to Donald Trump in the 2024 presidential contest. Many people recognize that the answer is multifaceted and combinatorial: a variety of influences, large and small, summed together to create an overall insurmountable barrier. Still, the debate rages on.

Personally, I want to bring to the table an aspect that I believe has gone undiscussed in these post-mortems. In fact, I think it’s crucial that we consider this particular facet of the campaign, because this factor will remain as a force into the future, and we need to be able to find an effective counter.

A lot of pundits have alluded to the fact or the impression that Harris did not focus enough on the working class this cycle. She didn’t zero in on “kitchen-table issues,” the commentariat has said. I don’t disagree — indeed, the working class needs always to be given priority in times where fascism is ascendent. Any neglect, insofar as it occurred, was a missed opportunity.

However, I reject the idea that this was what sank Harris’s campaign. The people who are complaining the morning after about “woke” issues getting in the way of policy are blind and mistaken. Those who use ‘woke’ in a non-ironic manner have already fallen prey to right-wing messaging. Their analysis is not too far behind.

On the other hand, you have folks who say it was Harris’s race and gender that did her in, to the exclusion of other factors. They lament that a Black female — or any female at all — may never ascend to the highest office. These people, newly suspicious of their fellow citizens, are ticked off at the electorate and bemoan the state of the union: are we all so blighted with racism and sexism that we’re doomed as a nation? Who are we? The election was a reflection, and they are not sure what they see.

Well, yes, race and gender had a great deal to do with why Harris lost. This isn’t rocket science (though, I admit, the statement is nearly unfalsifiable). We know, from this country’s long and storied history, how embedded discrimination against women and persons of color is in this nation as a whole. While we have gone through peaks and troughs in terms of tolerance, on the whole the United States has been relatively inhospitable to people from these groups ascending to leadership positions.1

I don’t subscribe to the idea that it was only race and gender that scuttled Harris’s chance at the Oval Office, but I do believe they played an intrinsic role in her defeat. That’s one of the reasons why I felt that Harris should be passed over as the Democrat’s standard bearer this cycle.

I got flack for this stance. People accused me, directly and indirectly, of being racist, sexist, or both. They tended not to have a response, though, when I noted the fact that I myself am a Black female and a lifelong Democratic voter.

It wasn’t just that I wanted to keep Harris down! That’s not it. But it strikes me that the people who were willing to attribute these traits to me were themselves the least astute at detecting these character flaws.

There was a focus group conducted by the Bulwark in July, after Joe Biden had stepped aside in the contest; of the people interviewed, notably it was Black Americans who cautioned that the country may not be ready to elect a Black female. Yet the party — largely White — charged on, confident that they’d be able to carry the day against all odds and historical indicators.

Hidden axis of attack

There was something about these factors, these immutable traits, that opened Harris up to attack in ways that Joe Biden could never be attacked. And it seems like political operatives and advisers wanted to pretend that the United States had advanced to a point where such factors would not be seen as an automatic negative. Apparently, they thought we were beyond that.2

I think that if Harris had run against the same two candidates that Obama had, John McCain and Mitt Romney, she would have stood an excellent chance at winning. Beyond the fact that those competitors were active before the Trump era (i.e., before political norms became warped), McCain and Romney themselves held a certain code of honor. It was beneath them personally to attack someone on the basis of immutable traits. McCain, notably, corrected a constituent in real time when she uttered of Obama that “he’s an Arab” (probably her idea that Obama wasn’t “one of us”). McCain didn’t let that slide; his honor wouldn’t allow him to do so.

That’s not Trump. Trump is not debilitated by such things as honor codes or a sense of fairness. And that goes beyond the ruthlessness that comes with the territory of being a businessman. (Even Romney, vulture capitalist, would not have sunk, I don’t believe, to the kinds of attack Trump used against Harris.)

No, Trump is a true believer in the inferiority of some people. We know this from the many statements he’s made over the years, particularly his comments about genetic heritage and about some genes being good or bad. This is a 21st-century eugenics statement, but Trump couches his language in soft enough terms that he flies under the radar for some people. But it’s clear that he thinks that some people are simply superior to others and that society should be structured that way, to reflect gradations of worth.

Trump doesn’t respect women. Trump doesn’t respect Black people. These are not controversial statements. And accepting these facts is key to understanding how it is that Trump was able to attack Harris in ways that he would never have been able to against a candidate who was (1) White and (2) male.

You have to understand that Trump is not a politician. He’s a salesperson.

This cycle, you had pundits rake Harris over the coals for not delivering a watertight, comprehensive economic policy. She could have brought to the table an incontrovertible hybrid of Keynes and the Chicago school and it would not have made a difference. Trump, her opponent, was not dealing in policy.

Trump was not trying to compete with Harris toe-to-toe. He meant to outsell her.

What was he selling? An attitude. An attitude of disdain, disgust, dismissal.

In the only debate between Harris and Trump, viewers noticed that Trump disregarded the opening handshake. It was only when Harris approached him and introduced herself that he engaged in the exchange. Throughout the debate, Trump never referred to Harris by name — he always reverted to ‘she’, and often he said the pronoun with barely checked contempt.

Much was said after the debate about Harris’s use of body language as a way of commanding control over the interaction. Harris was widely seen as the winner of the debate. But Trump also communicated through his choice of words and his intonation. He communicated a basic disrespect for his opponent.

This disrespect was not subtle. It simply wasn’t explicit. Yet his followers watching at home would have picked up on his cues and understood what he was signaling.

What is an attitude?

Hadley Cantril, in The Psychology of Social Movements (1941), defined an attitude thusly:

“[A] frame of reference is based on certain standards of judgment, and … an attitude emerges when a given situation is appraised by means of a frame of reference.”3

“People may react negatively to symbols, such as “Reds” or “W*ps,” or they may accept certain attitudes toward the season’s fashions, toward fat men, or blonde women — attitudes that have no discernible relationship to any underlying frame of reference. Such attitudes are essentially conditioned responses.”4

Attitudes specifically come to figure in the selling situation. Kenneth Hunt and R. Edward Bashaw in “A New Classification of Sales Resistance” (1999) spoke about a particular feature of the sales encounter:

“Included in the buyer’s schema is an attitudinal element. That is, when the buyer’s schema has been triggered, the buyer’s attitude (positive, negative, or neutral) toward the target of the schema is also triggered. Hunt postulated that a schema contains an ‘end node’ that is roughly equivalent to an attitude. This end node or attitudinal element of the schema influences the [individuals’] reaction to the stimulus (either positive, negative, or neutral).”5

A schema is a certain frame or script that one brings to a situation in order to make sense of it. The majority of those viewing the debate saw the interaction as one fitting into a schema about a presidential contest. These were two competitors, they’re seeking higher office, etc. However, what Trump signaled to his base was to basically throw out that schema and replace it with one much older and much more familiar to them: “I’m a White guy, she’s a Black woman. She’s naturally inferior to me. I’m going to treat her like that, and you should treat her like that, too.”

Thus Trump was not selling policies but instead a stance. And if people wanted to be like him, they would adopt his stance, too. In doing so, they could feel superior to Harris. They never would have to take her seriously — she was beneath them.

An end node, as Hunt has it, is the rough equivalent of an attitude. It is triggered as part of a schema. Schemas are long-standing, a feature shared with stereotypes. And, indeed, that’s exactly the type of schema that Trump tapped into: that of inferiority, where the stereotypes evoked are of racial inferiority on the one hand and gender inferiority on the other.

But these schemas do not operate independently, though we must conceive of them separately when analyzing them. In practice, however, they amplify each other, magnifying effects.6

Hitting the jackpot

Leon Festinger, who introduced the concept of cognitive dissonance, explained that there is a distinct similarity among different types of knowledges, attitudes being a type of knowledge:

“A person does not hold an opinion unless he thinks it is correct, and so, psychologically, it is not different from a ‘knowledge.’ The same is true of beliefs, values, or attitudes, which function as ‘knowledges’ for our purposes.”7

And many of us understand what confirmation bias is. When people encounter new information, they are more likely to accept it if it confirms a prior belief, or if it can be fit into the overall web of related concepts the person held beforehand.

Why is this? Well, people look for patterns. It is said that humans are pattern-detecting beings. We look for similarities of things we’ve encountered in the past, because we’ve survived all of our past encounters, so we’re on the lookout for things that will help us continue doing so. Most often, this is not a conscious pursuit. We are simply looking to confirm things so that we know that our environment is safe, in order for us to keep on existing.

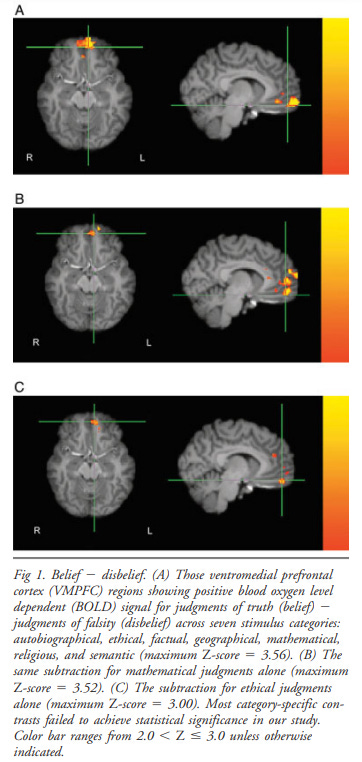

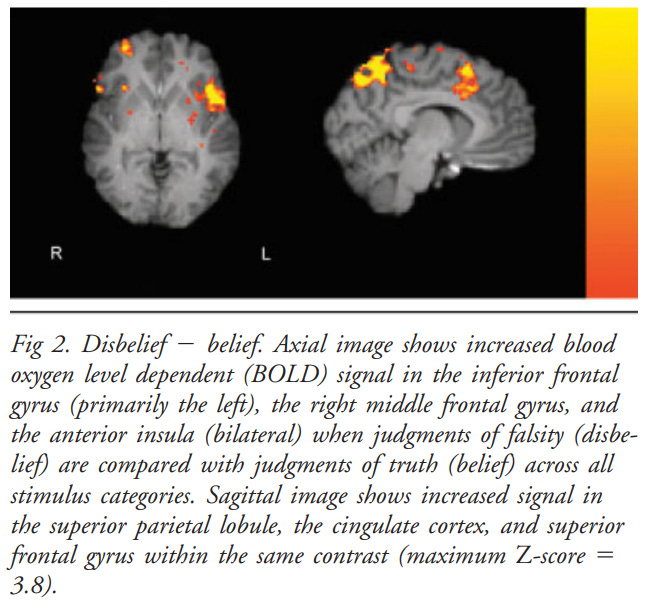

Belief is actually a pattern in itself. In “Functional Neuroimaging of Belief, Disbelief, and Uncertainty” (2008), Sam Harris and colleagues discovered that blood flow in the brain tended to differ under these states (belief, disbelief, and uncertainty). Generally speaking, in the state of belief, the person tended to have more activity in the very front of the brain, whereas disbelief tended to activate areas nearer the top and top-rear of the brain. (Uncertainty generated its own distinct pattern.)8

Thinking of belief in this way, one can view belief as pattern recognition. It’s matching the pattern of one’s brain state with patterns that had existed in the brain before that accorded with belief, with things that one took to be true. Thus the new information joins that category and gains that classification, as a true thing that one believes.

Basically, confirming a belief or attitude, neurocognitively speaking, is recognizing a slot machine striking triple 7s.

Racism as cocooned comfort

For people raised in a racist environment, to have someone “speak their language” confirms what they had been taught throughout a very formative period of their lives. Racism is a difficult schema to overcome because it’s used as a primary method of sorting the world.9 Hannah Arendt, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, said

“Few ideologies have won enough prominence to survive the hard competitive struggle of persuasion, and only two have come out on top and essentially defeated all others: the ideology which interprets history as an economic struggle of classes, and the other that interprets history as a natural fight of races. … [F]ree public opinion has adopted them to such an extent that not only intellectuals but great masses of people will no longer accept a presentation of past or present facts that is not in agreement with either of these views.”10

This remains true. In the West, the two grand organizing myths are that of race and of class. Racists have made their choice as to how they will sort the world, and anything that reinforces that schema tends to be accepted. Such reflexive reinforcement is precisely how stereotypes work. Walter Lippmann, in his classic Public Opinion (1922), described stereotypes and their role in shaping ideas:

“This is the perfect stereotype. Its hallmark is that it precedes the use of reason; is a form of perception, imposes a certain character on the data of our senses before the data reach the intelligence.”11

“There is nothing so obdurate to education or to criticism as the stereotype. It stamps itself upon the evidence in the very act of securing the evidence.”12

Evoking stereotypes — selling an end node — is how Trump won over his crowd. This isn’t to say that everyone who follows Trump is racist. However, chances are they’re not put off by his appeals to race as a way of seeing the world.

In terms of American culture, there are long-standing tropes that are ubiquitous. Many are interwoven into our very cultural practices and so are almost impossible to escape. Because of this proximity, people are able to recognize tropes when they encounter them. Trump made those tropes salient against Harris, and people who believe in those tropes responded favorably.

“[S]tereotypes are loaded with preferences, suffused with affection or dislike, attached to fears, lusts, strong wishes, pride, hope. Whatever invokes the stereotype is judged with the appropriate sentiment. Except where we deliberately keep prejudice in suspense, we do not study a man and judge him to be bad. We see a bad man.”

— Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion

Thus Trump was able to reference Willie Brown near the time that Harris entered the contest, which evolved into Trump’s proxies making much more explicit references, which led to Trump sharing a stage with someone who spoke about Harris’s “pimp handlers,” and which culminated in Trump simulating a sex act with a microphone. All of these invoked the same trope, reinforcing the idea of Black women being sex objects and good only for that act.13

Trump didn’t need to expend energy debating Harris as an equal. He could degrade her in attacks that never could have been launched on someone male or White.

It never made sense for the Democratic Party to run Kamala Harris as a candidate in this environment, where half of likely voters were in the mood for a strongman. The best we could have done was offer them an alternative that would have disarmed them through their own biases. “Hmm, here’s one White guy… here’s another White guy! Hmm! How are they different?” It’s at that point such voters would have been open to a policy argument, so as to make a judgment between them. Until then, claims about immigrants eating dogs and cats could rule the day, as that’s precisely how much policy didn’t matter.

Don’t point to Barack Obama as a disconfirming example. The exception in this case proves the rule.

Again, folks will point to Barack Obama. As someone said on another platform recently, Obama “was a f*cking unicorn.” Lightning in a bottle, I would say. We can’t hold him up as the benchmark or consummate comparison.

Cantril, Hadley. The Psychology of Social Movements (1941), p. 21. Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company: Huntington, New York.

Ibid., p. 23.

Hunt, Kenneth and R. Edward Bashaw. “A New Classification of Sales Resistance,” Industrial Marketing Management (1999), Vol. 28, No. 1, p. 111.

This is why the hybrid of race and gender stereotypes, as denoted in the term ‘misogynoir’ (misogyny against Black women), is a unique phenomenon, at least in American culture. Harris was not dinged just because she was Black; and she was not dinged just because she was female. There’s an intersectionality that comes into play that cannot be separated.

Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), p. 10. Row, Peterson and Company: Evanston, Illinois.

Harris, Sam et al. “Functional Neuroimaging of Belief, Disbelief, and Uncertainty,” Annals of Neurology (2008), Vol. 63, pp. 141-147.

Sexism works in a very similar fashion, though with specific differences. Genevieve Lloyd in The Man of Reason (1984) notes that even at the height of chauvinistic Western attitudes toward women, men understood that they could not segregate women from society totally. Unlike what can be done in a system delineated by race, a society could not replicate itself without females, so it’s impossible to excise them. Instead, females become adjuncts to society, providing unseen, unacknowledged labor (p. 77): “For Rousseau… women’s closeness to Nature made them moral exemplars, while at the same time it provided a rationale for their exclusion from citizenship. The containment of women in the domestic domain helped control the destructive effects of passion on civil society, while yet preserving it as an important dimension of human well-being. […] Rousseau’s solution, of course, was to make the men good citizens and the women good private persons.” (Kant and Hegel held to similar double standards. See especially pp. 74-85.)

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism (1948 / 1968), p. 159. Harcourt, Inc.: New York City, New York.

Lippmann, Walter. Public Opinion (1922 / 2020), p. 57. Digireads.com Publishing.

Ibid.

Likewise, all of the times that Trump and his surrogates remarked that Harris was “low IQ” or spoke in “word salad” and so they couldn’t understand her (even when she was speaking far more coherently than Trump) signaled to Trump followers that they should view her through that lens, seeing her as Black women have been seen through the vast majority of American history.

It’s been long apparent to me that discussions of sexism and racism in public discourse are crude to the point of uselessness. When someone calls someone else a racist, the interpretation of the term is that one is being accused of “not being nice” or “being a bad person.” This is in keeping with our hyper individualistic society, where the assumption is that there are no systemic problems, just individuals making good or bad choices. Therefore, if one doesn’t consider oneself to be racist, all you have to do is “be nice.” And if you are racist because you aren’t nice every once in a while, it was just a joke, so stop complaining. In reality, racism isn’t a matter of an individual intent of “being nice,” but is the result of systems shaping implicit and explicit actions.

Sexism is a bit different, since a lot of self-proclaimed liberals will fall into sexist behavior and thought patterns simply because patriarchal thinking is the default in society (eg having women do domestic labor without consciously agreeing to such an arrangement). But once again, people tend to boil it down to individual behaviors and not societal patterns. Lots of people seem to think that just “being a gentleman” is enough to combat sexism, when gentlemanly behavior was always aimed at certain classes (and races) of “respectable women.” The idea that systemic problems can be reduced by just “being nice” seems to be given by liberals and conservatives.

In and of itself, I think that willingness to vote for a Black woman for president is meaningless. Putting women and minorities in institutions soaked in white supremacy and sexism doesn’t change the nature of those institutions, it just socializes these exceptional cases into being part of the problem. I guess it would have been great for Harris as an individual if she had become president, but it wouldn’t have done much for the rest of us. The politics of representation essentially mean that we’re supposed to get off on psychological benefits, rather than material ones.

This is brilliant.