Israel has released a statement — one of many statements by now — about the World Central Kitchen workers killed, saying, at least in part, that the strike was a “grave mistake.” Those were the words of IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi.

This wording deserves scrutiny, as it’s manipulative and entirely disingenuous.

The disingenuity can be discerned by examining the facts on the ground:

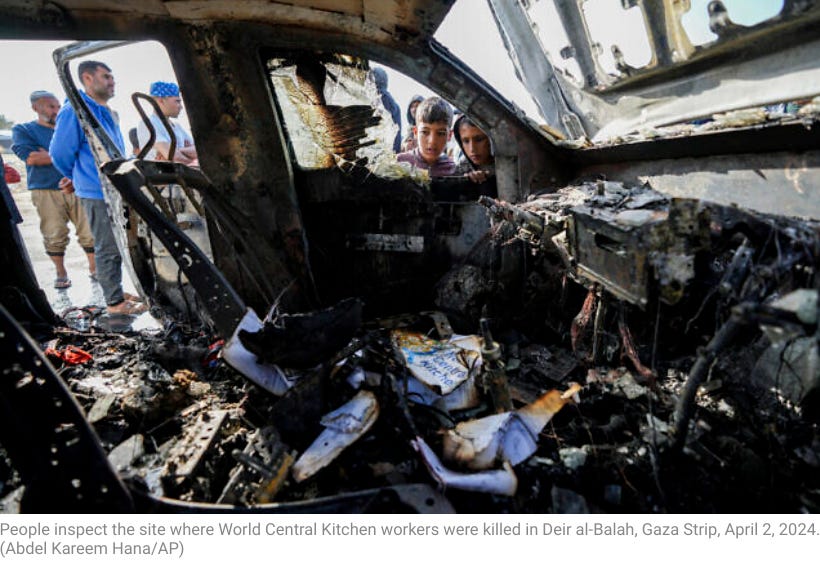

There were three vehicles in the convoy, and all three were hit in succession, not simultaneously, by multiple strikes.

The missiles originated from a drone controlled by a human, not AI.

The convoy was in a zone described as “de-conflicted” and WCK had received prior approval for the convoy’s movements — indeed, they had told the IDF of all of its movements and had provided their coordinates.

From reports, it appears a commander ordered the strike on the vehicles, whose identification — with roof-emblazoned logos — should have been clearly visible to the drone operator.

After each vehicle was hit, survivors evacuated to the nearest vehicle, and each time the team contacted the IDF to let them know that they had been fired upon. Still, each time, the next car received the next hit.

None of this can be described as a mistake (or “unintentional,” as Benjamin Netanyahu put it). Someone intended for this strike to happen.

But also egregious is the proffer of the phrase itself: “grave mistake.” On first glance, it would seem as though the phrase is one of commiseration, perhaps even contrition. But the words are not buttressed or followed by an admission of guilt, which would be in evidence were the words truly meant as a gesture of remorse or regret. (And, with Netanyahu’s blithe remark that “these things happen in war” when clearly they don’t negates the seeming acceptance of responsibility.)

What “grave mistake” does is signal that an apology is forthcoming or present, but in this case an apology has explicitly been ruled out (or, at least, actively avoided). Thus, all we have with this phrase is hollow form, words that imply something that is not there. It’s a pretense, spoken to make the person hearing the words believe an apology has been offered, though there’s no such thing.

There’s a profound but little-publicized social experiment from the ‘70s (one that I’ve described before) where the researchers wanted to find out just what the limits of social scripts might be. This is informally called the Copier Experiment. This involved sending strangers into a photocopying hut to interpose themselves between the copier and the person at the front of the line and to request that they be allowed to use the copier next.

One of the ways this request was conveyed involved what the researchers termed “placebic” information, words that filled the script of the social interaction but actually held no meaning.

“Excuse me, I have 5 pages (or 20 pages). May I use the xerox machine?”

“Excuse me, I have 5 (20) pages. May I use the xerox machine because I’m in a rush?”

“Excuse me, I have 5 (20) pages. May I use the xerox machine, because I have to make copies?”

The researchers had predicted that, if the listener were keyed into actual information, the middle request would get more yielding responses and that the third (needing to make copies, a redundant bit of information that was true of all of the people in line) would have a similar rate of complying with the request.

To the experimenters’ surprise, the “placebic” information, at least for the smaller amount of copies, elicited an identical amount of acceding to the request as to the one with substance.

The researchers surmised:

“[A]n interaction that appears to be mindful, between two people who are strangers to each other and thus have no history that would enable precise prediction of each other’s behavior, and in which there are no formal roles to fall back on to replace that history, can, nevertheless, proceed rather automatically. If a reason was presented to the subject, he or she was more likely to comply than if no reason was presented, even if the reason conveyed no information.”1

That’s what “grave mistake” here does for the consumers of Israel’s statement. These words normally indicate the presence of an apology, so the person hearing these words accepts them as though that’s what they are. It is an empty gesture. It is a pantomime.

“Through repeated exposure to a situation and its variations,” Langer and colleagues explained, “the individual learns to ignore and remain ignorant of the peculiar semantics of the situation. Rather, one pays attention to the scripted cue points that invite participation by the individual in regular ways.”

In other words, given a social script, we tend to pay attention to our role in the situation and what that role demands — our typical “lines” for a given “scene.” The scene here is one of purported condolences, and the listener’s automatic response is to accept them. And, because this is a script, the listener does this automatically.

That’s what this statement by Israel is meant to evoke. It’s a perverse form of public relations, one we should flatly reject.

Ellen Langer et al., “The Mindlessness of Ostensibly Thoughtful Action: The Role of ‘Placebic’ Information in Interpersonal Interaction,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1978), Vol. 36, No. 6, p. 638

It sounds like it was deliberate to me, and we should be outraged that Israel is trying to manipulate us this way while bombing aid workers.

This is brilliant, as are the comments. What we’re getting from Israel in this instance is a subtle form of lying. Many of their other lies are open and outrageous.